Ask any teacher, should your teaching match the learning style of each student? Almost guaranteed, they will answer an enthusiastic “Of course!”

The precept of neurodiversity supports this responsive attitude. All brains are different. Kids learn differently. Play to their strengths and support their weaknesses and we can help all children reach their potential.

While talented teachers all over the world adhere to this theory; plan for student diversity; and implement lesson plans with auditory, visual and kinesthetic aspects, there are still some sacred cows that many teachers just don’t want to let go of, responsive teaching and neurodiversity be damned!

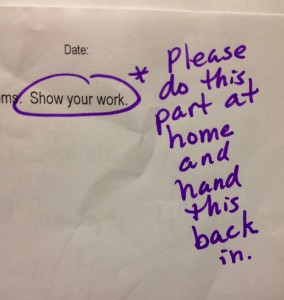

One of those sacred cows, near and dear to the heart of math teachers the world over? Show Your Work!

First off, let me say that in most circumstances, with most kids, this is a great rule. It shifts the focus from product to procedure, from correct answer to thinking process. It encourages meta-cognition. It allows the teacher to analyze the student’s thinking process for breakdowns, and makes it more likely that a student actually did the work to get the answer, rather than getting it from a friend, the back of the book or mom or dad.

But there are two groups of kids for whom showing their work can become the most painful part of their nightly homework. The rigid requirement to Show Your Work can actually interrupt the learning of kids with Dyslexia (especially those who also have ADHD) and kids with a certain style of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

What both of these types of kids have in common is a brain that makes intuitive leaps in a single bound.

According to Drs. Brock and Fernette Eide in The Dyslexic Advantage, on a neurological level, the dyslexic brain is tailored to grasp the big-picture more than the details. These kids often look challenged in math when the focus is on memorization and detail analysis, but with the proper support, they shine in Algebra and higher math. One of my former students, Franchesca* (whom I’ve mentioned before), could be a poster child for this phenomenon. Show her a one or two step Algebraic equation, and she’d leap to the answer. Ask her how she did it, and half the time she’d shrug and say, “I just figured it out. It’s obvious.” Ask her to write out all her steps all the time, and she’d glare at you as if you just asked her to scrub the bathroom in Central Station with a toothbrush, especially because she also had ADHD, which made repetitive, detail-oriented work torture for her. After butting heads a few times, having her explain to me again why she didn’t write out her work, I finally listened. So we compromised: she had to show her work on one or two of each type of problem; then, as long as her answers remained accurate, she could skip writing out all the steps for the others.

The case of kids with ASD is a bit more complex. We tend to think of ASD as a right-brain problem; most of these kids are left-brain, step-by-step, logic, detail-oriented type of thinkers. Right brain activity–creativity, socializing, and visualizing tend to be a challenge.

One subset of these kiddos, however, seems to have a, unusually strong ability to visualize abstract ideas. In fact, noted Autism advocate Temple Grandin’s autobiography is entitled Thinking in Pictures. According to her brain scans, this may be due to “enhanced’ connections…in the left precuneus, a region involved in episodic memory and visuospatial processing.”

Many biographies of Einstein note his remarkable ability to visualize the concepts he was exploring: his quest that ended in the theory of relativity started as a child when he asked himself what light would look like if one were riding a lightening bolt. Often, these kiddos’ amazing ability is obscured because they struggle to create a link between their developed, abstract pictures and the language to express them.

Facing a math problem, these students often find the solution with breathtaking rapidity, most likely based on the accurate, abstract visualization of the problem in their mind that makes the solution obvious. The problem arises when they are then asked to show their work. Let’s face it; we mostly left-brain teachers are asking them to translate their intuitive, right-brained, image-based work into very left-brained, step-by-step language.

We had a student with autism in a school where I taught, who had that kind of mind in math. He could intuit the answers to complex problems in one fell swoop, but had difficulty explaining his breath-taking leaps. In fifth grade, he ran into a teacher, quite talented in teaching math to typically gifted kids, who was very left-brain in her approach to math. She required kids to write their steps down and to construct written reflections about their thinking. Our not typically gifted student not only hated doing either; he often simply could not fully articulate how he made his leaps. Not surprising, since, well, kids with autism often have trouble connecting the pictures in their mind to language.

The teacher was chatting with me one day and said she would not let him go on to the next problem unless he wrote down all his steps. “You know,” she confided, “people say he is brilliant, but if he can’t explain how he got the answer, he doesn’t really understand the math.”

Ask this teacher if she respects neurodiversity, her answer would be of course. Ask her if she is responsive to different learning styles and she’d say always. And often she was. But in this instance, she simply could not fathom his understanding math in a way so incredibly foreign to her. Although her assertion that he “doesn’t really understand the math” was belied by his consistently getting the correct answers, she just couldn’t muster the mental flexibility to accept the full extent of his neurodiversity.

So no, I’m not advocating throwing out Show Your Work for most kids most of the time, because it helps most kids most of the time. But I am asking you to look critically at even this most cherished rule when you get a kid who chafes against it more than usual. Really look at why they are chafing. Is it your garden variety, “It’s hard and I don’t like to,” resistance, or is there a valid and compelling neurological reason why your flexibility with this requirement will be what helps your student achieve their full potential.

After all, no one wants to be the math teacher the next Einstein hated.

copyright Diana Kennedy 2014

Thanks for that post..it helps

[…] Mental Flexibility: It’s Not Just For Students Anymore! – a terrific article about flexible thinking for teachers from Diana’s own blog. […]

I have an ASD and this is what maths lessons always felt like to me.

problem: Find the value of 1+1

me: 2

teacher: You need to be able to show your working or you won’t get full marks for your answers in the exam. It’s all very well being able to do all these fancy calculations in your head, but you need to learn how to explain what you are doing and show that you understand the underlying concepts.

me: I don’t want to. I don’t care about exams. It’s all pointless. (commences pleading blackmail attempt) I’ll show workings if and only if you give me harder problems.

teacher: (now visibly seething) Redo the question and hand in your answer tomorrow.

my redone solution: ∀x;x=y⇒(x=z⇒y=z)

∀x;x=y⇒(x=z⇒y=z)⇒x+0=y⇒(x+0=z⇒y=z)

x+0=y⇒(x+0=z⇒y=z)…

…(after 52 lines)

(0’+0)’ =0”⇒(0’+0′)=0”

(0’+0′)=0” Therefore 1+1=2.

teacher: I can’t follow your answers. You need to be more explicit about some of the steps.

Lol! Exactly!

That being said, there is something to be said for playing the game of school, even if it makes little sense. But it would be better if there weren’t the games to begin with.

While your anecdote makes me smile, I have lived long enough to understand that, regrettably, the world will never conform to my child, so, unless my child learns how to conform to the world, she will always be at a disabling disadvantage. This causes me no end of distress. She will have to live in the world as it is, not as it should be. I have advocated for over 40 years and if I have 40 more, it will not be enough to even the playing field for her. I used to believe that change would happen in time for my child, but…. So, I am not interested in theoretical, intellectual exercises in understanding any longer, although I used to be and I know they serve a purpose. I just want her to be safe and reasonably happy. I have not found a way for that to be possible, yet. So, that’s where I will direct my energies. We can probably change the schools, but, until the world after high school changes, our kids are in trouble and at the mercy of whatever politician signs the budget funding the resources they need.

I hear you and feel for you and your daughter. While the world has not conformed and probably won’t very soon, there are more and more niches where a kiddo with ASD can find success. Silicon Valley is filled with successful folk on the spectrum. Just recently, there was a news story about the Israeli military using people with autism to help gather intelligence. “The autistic young men and women who serve in Unit 9900 can sit for hours in front of electronic maps spotting the minutest changes, Channel 10 said. This is a rare ability that eludes most non-autistic soldiers.” http://www.algemeiner.com/2014/02/20/idf-intelligence-unit-using-soldiers-with-autism-produces-stellar-results/ In a similar vein, SAP started hiring people with ASD “to fill jobs that require great attention to detail, such as testing software, debugging, and assigning customer-service queries.” http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2014/03/28/autism_at_work_companies_like_sap_and_freddie_mac_are_hiring_people_with.html

Of course, these are cases where special interests can be harnessed in a field that pays. But looking for a good-fitting niche can be incredibly valuable.

You miss my point. There’s more to life than a job. I can find a niche for her, but you can’t live in one niche.

I see. Yeah. It’s very hard. The more severe the impairment, the harder. I know a friend of mine who has high functioning autism found his group of friends through dungeons and dragons and has fit into that type of community ever since.

I am always very impressed by how hard-working, steadfast and fierce an advocate parents of all these kiddos are. It is a full time job in a lot of cases.

Has she done social thinking training (I like Michele Garcia Winner’s approach especially)? I assume she has done a lot of different things like that to give her the skills to be independent?

Keep up the good work!

Kids with ASD, dyslexia/ADHD, and dysgraphia/ADHD (which also makes showing work problematic but is not mentioned in this article) are ALREADY at a disabling disadvantage. The only way for them to not be disadvantaged is for them to be able to access their own thinking so that they can do the work they are capable of. As the wife of one of these kids and the mother of another, I find that it is much easier for people with learning differences to get by in life than in school because they can find their niche. The problem comes when they lose educational opportunities because, while their thinking is accurate and works for them, they are not able to think the “right” way. I’m pretty amazed at the amount of working memory my child has developed in order to compensate for her inability to draw graphs and write automatically (she’s dysgraphic). But she does not learn math at school. She learns it at home. She works the problems verbally. Once her math skills are ahead of mine, I don’t know how she will learn math.

Great insights. And yes, I missed dysgraphic kids. It just goes to show the enormous range of variability within the LD community. As you point out, your daughter and many like her are excellent in their verbal skills and do better with verbal mediation–it becomes their compensatory strength. For others, it is adding weakness to weakness. The best thing is to be sensitive to the individual needs, strengths and weaknesses of our kids and students and not confuse any one weakness for a lack of intelligence or ability.

My son has autism (high-functioning) and struggles with this very concept. He is in the highest math class for his grade level-pre algebra. He had been tested extensively and they has his visual-spatial reasoning is off the charts. Ask him to explain how he arrived at his answer is like asking him to fly to the moon…nothing will frustrate him faster. Great article…more teachers need to understand this!

Thanks. Feel free to share it with them.

Many teachers do. Unfortunately, the new Common Core standards require these explanations. Teachers don’t get to make up the curriculum or even the assessments that require same. Education administrators and policy makers must be made aware and create accommodations.

that’s a great point. I wonder if this is something that could be written as an accommodation in an IEP or a 504. I don’t know how the Common Core is going to affect all this.

You mention Dr. Grandin’s “Thinking in Pictures” however, her subsequent work, “The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum” discusses a type of autistic thinking qualitatively different from her own which she refers to as “pattern thinking”. I believe this may more accurately describe some of the kids who just “see” the answer to complex math problems. They can instantly recognize the patterns without going through the typical thought process that most NTs do. Thinking in patterns describes my kiddo better than thinking in pictures.

You know, that’s a great point. I clearly need to read that book as well. In The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, Oliver Sacks describes a pair of autistic twins who sit and come up with very large prime numbers–in the hundred thousands. He joins them (with his book of primes) and offers a few himself. After sitting quietly for a few moments to absorb or analyze the number he offers, a smile spreads on their faces. They clearly enjoyed the activity. He had no idea how they achieved this amazing feat. Later, a reader wrote in about a way of finding out primes using fractal patterns, which Sacks decides is probably how they did it.

It would be interesting to study how much overlap there is between the pattern-recognizers and the visual thinkers. For instance, the way the fractal/prime connection was explained, if you could understand the pattern, then you could visualize the fractal patterns of the numbers and see whether the prime was part of the fractal or not (I may not be doing the math justice, since it is beyond my understanding!).

They are also finding that autistic brains tend to have many more connections between neurons than NT brains, so a gift for pattern matching certainly makes sense.

Thanks for such a provocative insight.

Dr Grand in herself was surprised to find out about this different type of thinking. She reached out to others on the spectrum and tried to understand how their minds work. Its a good read! Thanks gir writing this blog. I’m trying to figure out how to share it without offending anyone.

As a teacher, cognitive rehabilitation therapist, social worker and mother of a 42 year old ASD adult, I found the article interesting in its implications for teachers whose goal is to have their students pass academic exams. It emphasizes the strengths of these unique learners. However, my concern is for the disabling impact of some forms of neuro-diversity. More is needed than to help increase academic achievement. It is a disservice to focus on strengths without offering ways to help overcome weaknesses, especially when these weaknesses result in a poor ability to function within the social, interpersonal demands of the real world. I applaud my daughter’s strengths, but I know that she is ill-prepared to live independently because of the weaknesses that had never been adequately addressed while she was in school and for which there are no services in adulthood. We must look beyond the high school learning needs and focus on what is really at the heart of their disability. There needs to be post high school resources to provide an extended period of learning and habilitation opportunities with the goal of fostering maximum independence and social competence.

Absolutely! Point well taken, and I completely agree. We need to strengthen strengths and remediate weaknesses. But we need to be clear which is which. For instance, making the kid I spoke about show his work will not help him connect words to pictures, because it isn’t a focused enough intervention for him. I would suggest intensive work with Lindamood Bell’s Visualize and Verbalize for a kiddo like this. That work strengthening the connections would serve him well in following directions, reading comprehension, writing clearly and with details, and in oral language comprehension. Perhaps after that intensive remediation, he would find showing his work easier. Perhaps not, but it would help in so many other ways, it would be worth it.

There is also a huge difference between high functioning autism and lower functioning autism. This kid was doing fine in school, was socially awkward, but no more than your average math and chess genius, and was going to be independent. If a kiddo is really struggling to be independent, then yes, she or he needs the support and remediation to be so. The one issue I would add is that often the strengths can override the weaknesses if given a chance. I’m thinking of Temple Grandin, who found her niche with working with cows *way* before she became a, advocate and spokesperson for autism.

And I guess this brings up the core of making any wide-spread comment about what should be done for people with autism. Autism is a very wide term and the people who have it are extremely diverse themselves. It is a fool’s errand, even limited to working within the autism community, to think that one approach will be the best practice for everyone who has an ASD. Which is why teachers really need to be flexible in their thinking! What is important for this particular kiddo to succeed, not just in 5th grade or high school, but as an adult? And what is trivial for them that I should just let go of? As long as teachers are asking those questions, then the kids will be better served.

Excellent article! Quite of few of my K-2 students with autism fit that picture.

Thanks, Van B. I agree–a lot of these kiddos can do math really well, but explaining it is a whole other matter.

Fascinating and instructive.