When we grew up and went to school,

there were certain teachers,

who would hurt the children any way they could.By pouring out their derision,

upon anything we did,

exposing every weakness, however, carefully hidden by the kids.–Pink Floyd

My friend’s voice vacillates between quivering with anger and with tears as she tells me a recent story about her daughter–an eager, hard-working second-grader whom we’ll call Cassandra–at a blue-ribbon Marin public school.

“The teacher sends home these four color-photocopies of magazine articles each week with the kids. Cassie loves them and reads through them diligently each week. Last week, she lost one. She looked everywhere for it. She was mortified, and really scared to tell her teacher about it. I went with her, assuring her it wouldn’t be that bad. So, she walks up to the teacher with her head down, and I am behind her, and she tells the teacher she lost one of the books and that she is really sorry.

“The teacher looks at her with an expressionless face, and says, ‘I’m very disappointed in you, Cassandra.’”

If I were in charge of the world, or at least of the school, the words of the teacher, whom we’ll call Mrs. Trunchbull, would be on the list of phrases not allowed in the school–the zero tolerance list. Why?

There is no room in a learning environment for shame. Ever.

We know that students learn best when their affective filter is down, when they feel safe in their environment–especially safe to make mistakes–when they feel a strong sense of self-efficacy and when they feel positively attached to their teacher. Shame attacks the foundations of each of these conditions.

Shame is different from guilt. Guilt disapproves of an action; shame disapproves of the person. Guilt inspires restitution; shame paralyzes.

In a 1993 study where children were given a toy rigged to fall apart, children with a guilt-orientation showed amending behavior: showing the broken toy to the adult, trying to fix the toy, or asking the adult to help fix the toy. Children with a shame orientation showed avoidant behavior: hiding the toy from the adult, avoiding attempts to repair the toy, and not making eye contact with the adult or participating when the adult tried to fix the toy.

When she says “I’m very disappointed in you,” Mrs. Trunchbull directs her opprobrium at Cassie the child, not the loss of the book. By choosing to shame her, Mrs. Trunchbull made it more likely that Cassandra would behave in an avoidant–that is to say, irresponsible–way in the future.

Not surprisingly, shame interrupts relationships, increases anxiety, envy, jealousy, loneliness, discouragement and anger and decreases interest, joy, excitement and empathy, (Shame and Anxiety in the Learning Process: Making Sense of Feelings, Mary C. Lamia, PhD, Learning and the Brain, 2014). If a teacher were trying her best to destroy the optimal conditions for learning, she could choose no better path than shaming her students.

Shame’s Evil Twin: Punishment

So we know that by shaming Cassie, Mrs. Trunchbull decreased the likelihood that next time Cassie would take responsibility for her mistake through amending behavior. Why own up to a mistake if your apology won’t be accepted, there is no way you can repair your mistake, and you yourself will be rejected by your teacher?

Furthermore, because shame sees mistakes as reflections of a defect in the child, making amends is beside the point. It is not the behavior or its effects that are bad, but the child, so the only remedy is punishment.

“I’m very disappointed in you, Cassandra.” Mrs. Trunchbull continued, “From now until the end of the year, you will only be allowed to take home three of the weekly magazine articles instead of four.” This was in early October. That’s eight months of punishment for one mistake.

My friend stammered, “Well, could Cassie pay to replace the one she lost?”

“No. That is impossible. These are photocopied. They take time to make.”

“Well, could she come in at lunch or after school and help photocopy a replacement and pay for the cost?” My friend had trouble believing the teacher would offer no means of reparation.

“No. That is impossible as well.”

The thing is, we know punishment does not work in the long term. Punishment is most effective at getting children to hide their behavior and much less effective at getting them to change it. In his book The Myth of the Spoiled Child, Alfie Kohn cites a slew of studies that show that punitive parenting is more likely to produce children who are more aggressive and disruptive with their peers, have more anxiety and are less helpful and sharing.

Why would Mrs. Trunchbull shame and punish Cassie in order to make sure she would not lose another book when we know that shame and punishment are likely to have the exact opposite effect?

Unfortunately, some teachers rely on shame as a tool in their tool belt of psychological control. Kohn writes, “Psychologically controlling parents don’t just coerce children to make them act (or stop acting) in a particular way; they attempt to take over their children’s very selves…Love and acceptance are made contingent on pleasing the parent. Care, in effect, is turned into ‘positive reinforcement.’…It’s harder to fight this than it is to rebel against the overt regulation of one’s behavior,” (p. 62).

Substitute teacher for parent, and Kohn is describing Mrs. Trunchbull’s teaching technique, a technique that relies on shame and punishment.

The criticism of the child rather than her behavior makes the teacher’s acceptance of the child conditional. The withdrawal of love or acceptance is used as a punishment for being “bad.” The teacher’s love and acceptance then becomes the prize for being a “good” child. This creates a fear of abandonment, a lower sense of self-efficacy, and “a continual longing for the missing unconditional parental appreciation and affection,” (p. 63).

Psychological control is “subtler but more intrusive and perhaps even more damaging,” than behavioral control, such as physical punishment. Brian Barber found that psychological control is more likely to produce internalized problems such as depression, in addition to externalized problems like delinquency. It also leads to more anxiety, especially about abandonment, lower feelings of self-efficacy, as well as “dependency, alientation, social withdrawal, low ego strength, inability to make conscious choice, low self-esteem, passive, inhibited, and overcontrolled characteristics.” (p. 62). Psychological control undermines exactly the qualities in a child what we know make him an effective learner and student. All in the name of increasing the teacher’s control of him.

Unconditional Positive Regard

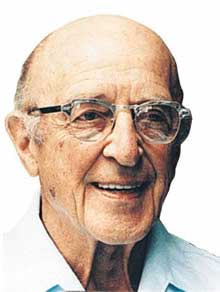

“The more I can keep a relationship free of judgment and evaluation, the more this will permit the other person to reach the point where he recognizes that the locus of evaluation, the center of responsibility, lies within himself.”

― Carl R. Rogers, On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy

So what is the alternative to Mrs. Trunchbull’s triumvirate of shame, punishment and psychological control? Permissiveness? Anarchy?

Far from it. The alternative is, thankfully, alive and well around us in many forms and under many names. Restorative Justice, Responsive Classroom, Attachment Teaching, Collaborative and Proactive Solutions, Trauma Sensitive Schools, Teacher Effectiveness Training…All take a humanist approach to classroom interactions and acknowledge the importance of the relationship between the teacher and the student as one of, if not the, most important elements in a positive, productive classroom.

I want to look back to one of the fathers of the Humanist psychology movement as one key influence in this movement: Carl Rogers. Even though teaching is not therapy, it can certainly be argued that they have overlapping goals: to support individual’s ability to fulfill their highest potential. Rogers came to believe that one of the three necessities in effective therapy, and perhaps the most important one, was unconditional positive regard (UPR). This does not mean full approval of every action a person takes, but that no matter what they do, the therapist (or teacher) continues to see the person as trying their best to move towards growth, health and self-actualization. Poor decisions, hurtful actions and mistakes are to be understood to come not from a general badness in the person, but from circumstances, misunderstandings and difficulties the person is having.

In educational terms, Dr. Ross Greene echoes Rogers’ assumptions in the basic supposition put forth in his book Lost at School: “kids do well if they can,” (p. 10).

This is the opposite of psychological control, wherein love and acceptance are explicitly conditional, and mistakes and shortcomings are seen as stemming from inherent flaws of the individual.

The difference in understanding leads to different reactions. With UPR, a mistake like losing a book is one to be jointly problem-solved by the teacher and the student. There is no shame, because the core goodness of the human being is not in dispute. Punishment makes no sense because there is no evil to be punished–just a situation to be rectified. Behavior can still be addressed, but it will be done in such a way that 1) it is the behavior only that is judged, 2) the focus will be on repairing any damage done and 3) the dignity of the student will be maintained.

Does Unconditional Positive Regard Work to Address Behavior?

Carl Rogers found, and research has attested, that UPR makes it possible for a person to change. In psychological terms, it lowers their defense mechanisms; in educational terms, it lowers their affective filter. While shame increases avoidant, irresponsible, behavior, UPR increases amending, responsible, behavior. While Mrs. Trunchbull explicitly rejected any attempt to make matters right, these humanist philosophies focus on giving students the tools to repair any damage they have done, as well as helping them learn the skills and techniques to make fewer (or at least different!) mistakes in the future. While psychological control and shame destroy children’s sense of self-control, self-efficacy and self-motivation, UPR increases each of those qualities. While psychological control grants and withdrawals the connection with the teacher, the humanist approach privileges the relationship between the teacher and the child and makes it unconditional.

The Only Zero-Tolerance Policy That Might Make Any Sense

The move away from the Mrs. Trunchbulls of the world and towards a more humanist approach can be seen in the recent wave of moves against zero-tolerance policies in school (and against their big-brother policies, the tough-on-crime strategies popular in the 90’s). Zero-tolerance policies are rooted in punishment and psychological control. They punish students for mistakes, rather than helping them build the skills and understanding to avoid mistakes in the future. They view students as potentially unredeemable and disruptive behavior as proof of an inherently bad nature. Cross X line, they say, and the community will reject you as unworthy to be among us.

In retrospect, such policies have been shown to be damaging, unequally enforced, and ineffective. They are being replaced throughout schools by more humanist policies that seek to work with students to give them the tools they need to improve their behavior. Far from making schools less safe, these policies are making schools work better for everybody without alienating an entire group of students seen as too bad to stay.

If I were in charge of the world, or a school, the only thing for which i would have zero tolerance would be teachers who use shame, punishment and psychological control in their classrooms. I would have zero tolerance for statements like “I’m disappointed in you,” “You are stupid,” or “You will never learn X/never be able to X/never succeed at X.”

However, if I am to be true to my own philosophy, I cannot assume that the Mrs. Trunchbulls of the world are willfully trying to damage children because of an inherently evil nature. I do believe that they are making the best choices they can, given their own understanding of themselves, children and the way the world works. Carl Rogers himself wrote, “The degree to which I can create relationships, which facilitate the growth of others as separate persons, is a measure of the growth I have achieved in myself.”

So, to apply the humanist policies even to the Mrs. Trunchbulls of the world, as principal of the school or ruler of the world, I would need to provide them with the tools and understanding needed to react differently and more supportively to their students, and I would need to do so in the context of unconditional positive regard, rather than rejecting them as too bad to remain in the community and thence barring them from teaching forever.

And in fact, the difference between schools that have succeeded in shifting their paradigm from punitive, shaming and controlling to helping and supporting students, and those where teachers are pushing back on the changing policy is the amount of training and support the teachers are getting to make these changes. The shift must be systemic and include the way principals and administrators view and treat teachers as well as the way teachers view and treat students.

Of course I am not in charge of the world, nor alas the school where this particular Mrs. Trunchbull expressed her disappointment at this particular little girl. So all I can do is listen empathically to my friend and hope that she and her husband have been able to build a strong and resilient girl who feels enough unconditional love and acceptance from her parents and her community that she is not too wounded by her teacher’s insensitivity. And to hope that her insensitive teacher can heal from her own wounds enough to stop passing whatever shame is hers onto the little people who rely on her for love and acceptance during their second grade year. And finally to hope that we, as a community in Marin, California and in the country, can choose to believe that all our children are not one mistake away from being bad, but to see them in the light of unconditional positive regard.

[…] Posts How to teach students who are too [insert emotion] to learn The only zero tolerance policy that may make sense Games: Soothing the […]