I recently went on vacation, so I’m once again aware of quirk I have speaking foreign languages.

I can have a reasonable conversation in Spanish, but in French, even though I can plan elaborate sentences in my head, as soon as I try to speak, I choke and devolve into a kind of Frenglish-sprinkled mime.

The thing is, I studied French, like, six and a half times longer than I studied Spanish.

So why do I make due in Spanish but freeze in French?

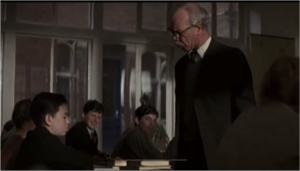

Well, my middle and high school teacher scared the bejeezus out of me. One day she’d be nice and encouraging, the next she’d be shaming and hyper-critical. You’d speak and she’d stop you a hundred times to correct little mistakes, judgment dripping from her voice. Some days, she’d dole out praise for your writing, the next day your paper would be covered in red ink. Insights into French culture were always tinged with disdain for the inferiority of American students, a version of “When I was a kid…” mixed with “American education makes you students soft” kind of rant. I never once got the sense that she actually liked us very much.

French was the only class in which I ever needed tutoring. I ended up with the sense that not only I was terrible at French, but more globally challenged at learning foreign languages.

I can barely describe the sheer terror that grips me when I try to speak French. This sense of deficiency survived college, even though my first year professor reassured me that I was actually very strong, and despite consistently good grades. It survived teaching French for two years in Mississippi (that’s a whole other story for a whole other post). And it turns my stomach when I try to speak French on vacation.

I learned Spanish one summer in Guatemala. The instruction was personalized, and the teachers personable. They were encouraging and excited and we had a lot of fun. So when I meet a Spanish speaker, I wade into conversation and don’t lose confidence even when I don’t know a word or can’t remember the conjugation of a particular verb. I joke about my mistakes, rather than being paralyzed by them. And interestingly, when I am trying to speak French and can’t remember a word, I often pull out the Spanish one instead.

This is my most convincing personal experience of the power of emotions in teaching. As it turns out, I am actually quite good at picking up languages; it wasn’t my ability but my anxiety that was the problem.

I have written before about the neurological processes that happen in your brain with anxiety, but it’s worth recapping here.

Human brains can basically be separated into three sections: the rear brain, sometimes called the lizard brain; the midbrain, or mammalian brain, and the frontal cortex, which is unique to primates. The more developed the frontal cortex, the higher the primate, with humans having the most developed one.

The rear brain is associated with the limbic system, the system that responds to very basic emotions, primarily fear. The midbrain generally deals with the more subtle emotions. The frontal cortex houses reasoning and higher order and abstract thinking, including the ability to think about the past and the future. Academic success relies on a sharp and functional frontal cortex.

Enter anxiety and a little structure in the brain called the amygdala. The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped structure that bridges the frontal cortex and the rear brain. It is the gateway to the limbic system. Its job is to decide where information goes in the brain. If you feel safe and secure, it stays calm and information goes to the frontal cortex, where you can spell, do math and conjugate verbs. If you feel under threat, the amygdala lights up and sends the information to the rear brain. The front brain shuts down and the rear brain chooses between three choices and three choices only: fight, flight or freeze.

Now, this was really useful back when our ancestors had to react to, say, a charging saber-tooth tiger. You don’t actually want to waste any time in analysis at that moment. You don’t want to stand there thinking, “My, that tiger is bigger than the last one I saw. While that means it may be more deadly, it may mean it is slower. I wonder if it can climb trees?” You’d be saber tooth tiger lunch long before you made up your mind.

The problem is that your amygdala can’t tell the difference between a charging saber tooth tiger and trying to speak French in front of an unpredictable, hypercritical teacher.

Anxiety makes it much harder to learn. Stephen Krashen called this the affective filter in his groundbreaking second-language acquisition research in the early 80’s. If a student’s affective filter is up, no learning will take place. If the affective filter is low, then the student can learn.

I didn’t have the words for it in middle and high school, but my French teacher kept my affective filter higher than any other class I have ever taken. Thence difficulty learning French, and my choice to start fresh in college.

What I didn’t realize until my honeymoon in France ten years ago, that affective filter/amygdala response was bound neurologically to French, which still triggers my anxiety response thirty years later.

You may have heard the phrase, “The neurons that fire together, wire together.” The fact is that anxiety and feelings of failure are literally interwoven with the French language in my brain. As surely as Pavlov’s dog salivated when he heard a bell, I am flooded with anxiety when attempting to speak French. And aren’t we lucky? Negative associations imprint much stronger than positive ones.

This is a sobering realization for an educator. In addition to the content, skills and processes that we impart to our students, we impart the emotions and attitudes they will carry with them about that subject, often for the rest of their lives.

How many of us can trace our love of a subject back to a special teacher whose enthusiasm was contagious, feedback was encouraging, and treatment of us was positive, understanding and even loving? Heck, I chose to major in Comparative Literature rather than English Lit because of one such professor, despite the fact that the choice necessitated an extra year of French capped off with a competency exam.

And how many of us still shudder when we think of a particularly mean or judgmental teacher, a teacher who may have even ruined an entire subject for us? My sixty-something year old sister told me about a middle school teacher who angrily accused her of faking her math difficulty just to get out of work. He was so negative that he transformed her confusion into a full-blown math phobia. Her subsequent anxiety shaped the rest of her academic career. Worse still, a few years ago she was asked at a job to sort a pile of envelopes by zip code. Her anxiety burgeoned into terror at the thought that she might possibly make a mistake on this simple task, which triggered her amygdala, sent her straight into her rear brain, shut down her forebrain, spiraled into a full-blown panic attack and made it impossible to complete the task.

The adults in a child’s life, whether parents or teachers, have the ability to set the tone when a child makes mistakes or faces challenges. Knowing that the emotional state, and particularly the level of anxiety, of a child dramatically affects learning, as well as the ability to recall and apply that learning later in life, should give us pause. So the next time you have the choice between chiding a student or encouraging one, being patient or being shaming, remember their amygdala, take a deep breath, and do what you can to lower their affective filter and give them a safe environment and a positive learning experience. Help them embrace and learn from their mistakes. Approach teaching with a growth mindset, in Carol Dweck’s words, and help them develop their own. Make learning fun and laugh a lot with them, since laughter beats out stress better than anything else. Above all else, don’t be their saber tooth tiger.

This post was so useful to read! As a teenager still progressing through education I relate to the situations mentioned so strongly and it feels amazing to have an explanation for freezing and anxiety within my learning. Thank you!

I’ve met teachers and professors who have pretty much given me hope after I fell out of love with becoming a pre-med. Big shout-out to a late brilliant-yet-psychotic chemistry professor from Chicago that I became a chemistry graduate student instead. Personally, I’m all the better for it. Which explains my attempt at high school teaching. Never won any teaching awards in four years, but all of my AP students passed the AP Chemistry, and I was still the most popular teacher.