What if we assumed that all children are good, no matter what their behavior? What if we assumed they never deserve to be punished or shamed for their actions? What if there was a way to address their negative behaviors through empathy, love and unconditional positive regard?

Current Crisis in Education: Puritan Paradigm and Empathy Paradigm

We all know that the US has an educational crisis on its hands. Depending on your view of children, you may think the crisis stems from a lack of high standards, or from the unreasonably high standards of the common core; from too much recess, or not enough; from too strict an environment or too permissive a one; or from parents expecting schools to raise their children for them, or from helicopter parents micro-managing every aspect of their child’s lives.

Putting aside the fact that every generation from Socrates’ time has thought they were living in the middle of a crisis in education, that they grew up in the best of times and their children are growing up in the worst of times, I think we can all agree that we as a society could be doing better by our children.

I would like to frame the current crisis in terms of two competing paradigms that I am calling the Puritan paradigm and the Empathy paradigm. I am further going to argue that to solve this current crisis, we need to purge the Puritan from our schools and embrace empathy and all that it implies.

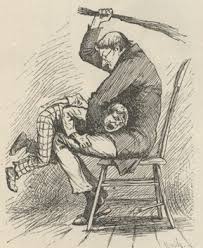

The Puritan paradigm that plagues our schools sees children as either Good or Bad, worthy of help or deserving of failure, in need of reward or of punishment. Adults constantly judge to which category a child belongs. This black and white view smacks of the Puritan’s constant struggle to discern who among them was predestined for heaven and who for hell. It does not judge a child’s behavior so much as his or her very soul.

The Empathy paradigm, in contrast, assumes that all children are good, that all children strive to do their best, and that if they don’t, something stopped them, something that can be addressed through a joint problem-solving partnership between adult and child, based on empathy, a strong adult/child relationship and unconditional positive regard.

Puritanical view of child

Conflate child and behavior

Recently a friend called me, her voice vacillating between anger and tears as she told me a recent story about her daughter–an eager, hard-working kiddo whom we’ll call Cassandra–Cassie for short–at a blue-ribbon public school.

“This teacher sends home four little magazine articles each week. Cassie loves them and reads them diligently every week. Last week, she loses one. She’s scared to tell her teacher. I go with her, assuring her it won’t be that bad as long as she takes responsibility for it. She walks up to the teacher with her head down and tells her that she lost one of the magazines and that she is really sorry.

“The teacher looks at her with an expressionless face, and says, ‘I’m very disappointed in you, Cassandra.’”

This teacher, whom I will call Mrs. Trunchbull (fans of Roald Dahl will know why), is the perfect representative of the Puritan paradigm. Intolerant and unforgiving of mistakes, her reaction makes no distinction between Cassie’s behavior and Cassie herself. She says, “I’m very disappointed in you,” not “I am disappointed that the article is lost.”

Punishment

When adults fail to make the distinction between child and behavior, they judge of the worth of the child. Puritan-like, they ask themselves, is this child Good or Evil? Do they deserve sympathy or punishment?

When adults fail to make the distinction between child and behavior, they judge of the worth of the child. Puritan-like, they ask themselves, is this child Good or Evil? Do they deserve sympathy or punishment?

What is punishment really about? Not the child’s behavior. Behavior can be analyzed and addressed. Teachers can guide students to make amends and build the skills necessary to improve in the future. No. Punishment communicates to a child that it is not their behavior that is unacceptable, but the child themself. Their behavior makes them unredeemable; there is nothing they can do short of suffering punishment that will make things right. Like the biblical scapegoat, they must be run off the cliff to purify the community of their sin.

To return to Cassie’s story, Cassie offered to pay for the lost magazine, but Mrs. Trunchbull refused. She also refused to let her photocopy a new one. Instead, she punished Cassie by limiting her to three magazines per week instead of the customary four. She originally set this punishment for the rest of the year. After Cassie’s mom pleaded with her, she shortened the sentence to through Thanksgiving. This was late September.

Punishment’s Evil Twin: Shame

Every week until Thanksgiving, Mrs. Trunchbull put a bright red paper in Cassie’s folder to remind her that the article was not returned. Cassie told her mom, “She knows it’s lost. Why does she keep sending these notes home?” Not that I would ever make a parallel between a big red note and, say, a scarlet letter A, but…Since punishment aims at the core of a child, it almost always is paired with shame.

Shame is different from guilt. Guilt disapproves of a behavior; shame disapproves of the person. Guilt inspires restitution; shame paralyzes.

In a 1993 study where children were given a toy rigged to fall apart, children with a guilt- orientation showed the broken toy to the adult, tried to fix it themselves, or asked the adult to help fix it. Children with a shame orientation hid the toy from the adult, made no attempt to repair it, and avoided eye contact and refused to participate when the adult started fixing it.

So, does punishment and shame work to curb unacceptable behavior? Far from it. By punishing and shaming a child, teachers make it more likely that their child will not take responsibility for their actions in the future.

To make matters worse, shame interrupts relationships, increases anxiety, envy, jealousy, loneliness, discouragement and anger and decreases interest, joy, excitement and empathy, even in the children who simply observe the punishment and shaming of a classmate (Shame and Anxiety in the Learning Process: Making Sense of Feelings, Mary C. Lamia, PhD, Learning and the Brain, 2014).

All the research tells us that students learn best when they feel safe in their environment– especially safe to make mistakes–when they feel a strong sense of self-efficacy and when they feel positively attached to their teacher. Shame attacks the foundations of each of these conditions. If a teacher were trying her best to destroy the optimal conditions for learning, she could choose no better path than punishing and shaming her students.

So what is the alternative to Puritanical Mrs. Trunchbull’s punishment and shame? Permissiveness? Children run amok? Anarchy?

The answer is no, no matter how much the Puritan view of children predicts just that. We know there is a more effective, kinder alternative because we see it making a positive impact every day in schools scattered across the nation. The alternative is the Empathy paradigm.

Empathy Paradigm

This paradigm goes by many names– humanist education, progressive education, Attachment Teaching. It is embodied in many programs: Restorative Justice, Responsive Classroom, Collaborative and Proactive Solutions and Trauma Sensitive Schools, to name a few. All embrace the Empathy paradigm, and all have had remarkable success.

Behavior versus child

The Empathy paradigm does not rely on punishment or shame because the core goodness of the child is never in dispute. No evil need be punished; a situation need be rectified.

Inappropriate behavior is addressed such that 1) only the behavior is judged, 2) the focus is on repairing damage done and helping the student to develop the skills to do better in the future and 3) the dignity of the student is maintained.

Behavior communicates

The separation of child from behavior implies that all behavior communicates. Negative behavior communicates that some obstacle is keeping the child from living up to her or his potential. Perhaps she lacks emotional regulation, or the language skills to resolve a conflict productively, or the intuitive understanding of social cues that would inform positive interactions with peers and adults. Just as we don’t blame a child with dyslexia for struggling to read and write, we shouldn’t blame a child for struggling with their behavior. Instead, teachers help students develop the skills to behave positively.

Teacher/Student relationships

When I started teaching, I was told many times that a teacher should not smile before Christmas. This puritanical tenet assumes that a positive relationship between teacher and students will lead to chaos and out of control children; the kind teacher will be sorry.

It is the nature and quality of teacher-student relationships that create the possibilities of learning

To the contrary, Louis Cozolino, psychologist and author of Attachment Teaching, points out that because humans have evolved to be social creatures and because our frontal cortexes continue to develop long after birth, relationships trigger neuroplasticity– the growth of neurons that embody learning. In other words, he writes, “It is the nature and quality of teacher-student relationships that create the possibilities of learning… “Teacher-student attunement isn’t a ‘nice addition’ to the learning experience, but a core requirement.” Empathy teaching prioritizes the positive and strong relationship between teacher and students.

Unconditional Positive Regard

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.

Carl Rogers famously said, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.” This was the guiding light of his therapeutic approach, what he called Unconditional Positive Regard. The same is true for the children teach. The more we accept them unconditionally, the more they can develop and grow. Rogers makes clear that this Unconditional Positive Regard is not the same as condoning a person’s every behavior; it means that no matter what their behavior, we still see them as a good person. The same is true in Empathy teaching.

Since I started with the story of Mrs. Trunchbull, I want to end with the story of the best teacher I ever had, Mr. Briley, my high school history teacher. While he was an excellent educator, it was not his ability to impart knowledge that made him my favorite. It was that he embodied the Empathy paradigm like no other: he consistently separated the behavior and performance of the students from the students themselves. He never punished or shamed us; he helped us become our best selves through loving guidance and understanding. He carefully tended his personal relationship with all students. He was one of those rare teachers who made it clear he loved us and supported us no matter who we were or what our behavior. We all felt it, from A students to C students, students with a predilection for history and those whose interests lay elsewhere, students who loved school and those who hated everything about it–well, everything but Briley.

We all knew in our hearts that he was not just our teacher, but our advocate and ally, that he was in our corner, come what may. We were safe in the knowledge that in the great struggles of adolescence with its shifting identities and alliances, he was on our side.

Period. End of story.

How did we know this so surely? Perhaps it was the rumors of a disciplinary meeting where he literally barred the door to keep the rest of the faculty from leaving when they had decided to kick an eighth-grader out for bringing alcohol to a school dance–the fact that her parents were in the middle of an ugly divorce seemed irrelevant to many of his colleagues. Perhaps it was the fact that he listened to our problems with empathy. But we knew his acceptance of us miraculously had nothing to do with our last test grade or our last essay. In the school context where all regard seemed conditional, Briley blessed us with the greatest gift a teen could ask from an adult: unconditional positive regard.

It is in Briley’s name that I dedicate my mission to purge the judgmental, punitive, shaming rod of the Puritan from our schools and replace it with the gentle guidance of an Empathy that accepts all children as good, problem-solves with them to help them reach their highest potential, and bathes them in the unconditional positive regard that shows our faith in them. And that, my friends, is how we solve today’s crisis, not only in education, but also in our society and the world.

As always, Diana, you expressed the essence of a true teacher and of a lover of children!

Thanks! That’s very much appreciated. Good to have like minds!