“Come on, Philip. Don’t complete all the worksheets now or you won’t have any for homework!”

How often do you have to say this to a student? Much less steal away the one remaining uncompleted worksheet to hand to Mom because a) your student is finishing the penultimate worksheet you handed him for homework and reaching for the final one and b) it’s five minutes past time for your session to end? All I can say is there are definitely worse problems to have with a kid.

So, you ask eagerly, what type of magical worksheet is this that motivates a student so thoroughly and completely? It must be beautiful and creative and spectacularly fun! Tell us the secret!

Well, as Kung Fu Panda discovered, (you have seen Kung Fu Panda, right?) the secret is there is no secret. Simply put: nothing motivates like success.

Philip is a bright kid with complex learning disorders that were just recently diagnosed; he has experienced a good amount of previously-unexplained failure. He is curious, bright and enthusiastic, yes, but he also has a shaken self-confidence, especially in the area of math, where we work.

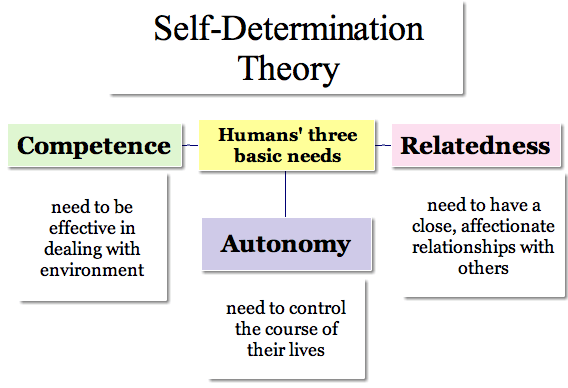

When we look at the science of motivation, giants in the field Edward Deci and Richard Ryan have identified three things that motivate humans. Spoiler alert–rewards and punishments are not among them. They are autonomy, relatedness and competence, or in Daniel Pink’s slight variation: autonomy, purpose and mastery.

Let’s look at the last ones–competence and mastery. A student with a learning disability rarely feels competent at school and rarely reaches mastery. It is really hard to stay motivated when it feels like all your hard work leads nowhere, especially when you can see most of your peers improving when you aren’t. Then to add insult to injuring, many of the adults in your life tell you that you just need to work harder. Time to check out. Why even try?

Enter the magical worksheets. Well, actually, the worksheets came last after a lessons with base ten blocks, a hundreds chart and hundreds chart puzzles, and a color-coded recording sheet for two-digit place value.

After a few days of finding a single digit number on the hundreds chart, building it out of base-ten blocks, recording it on the place-value chart and then adding a ten and going through the steps again (for a complete description of the lesson, see Two Birds with One Stone: Adding Tens), we added the hundreds chart puzzles. After a few more days going through the whole sequence with the hundreds chart puzzles as the climax, I brought out The Worksheet. Pretty boring, really. Your standard grid of problems, all of them a single digit plus ten or, for variety, ten plus a single digit.

“NO! I’m not ready for these,” Philip moaned. “Let’s keep doing the puzzles. I’m good at those!”

I show Philip how to fill out the worksheet with the hundreds chart. “Oh! Easy breezy!”

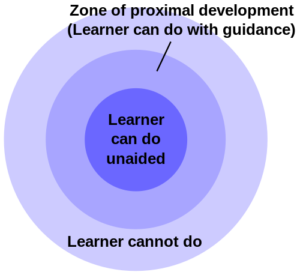

Let me interrupt myself quickly. Notice that I had to introduce Phillip to the concept with extremely small increments. This reflected both the severity of his math learning disability as well as the shakiness of his self-confidence. Had I tried to move faster, before he felt a sense of mastery, or had I tried to skip a step, he would have shut down, once again reaffirmed in his self-identity as someone who could not learn math and who was stupid, no matter how many adults told him otherwise. Educators talk about a student’s Zone of Proximal Development, the space between what they can already do independently and what they can do with instruction.

For some kids, that zone is pretty wide–they can make pretty large jumps without undue frustration or confusion, filling in a few missing details here and there on their own. For a kid like Phillip, the zone is very thin and each step forward must reflect that. Had I jumped too far, I would definitely have needed to back up and make the increments smaller and the practice longer.

Back to Phillip. The day after we fill out the worksheet with the hundred’s chart by our side, I cover up the hundreds chart.

“Diana!!!” Philip protests loudly.

“Ok, I’ll show you the chart in a second. But first, let’s see if we can predict the answer.”

“I can’t!”

I gently show Philip how these worksheets are really the same thing as the hundreds chart puzzles, which were the same thing as the base-ten blocks. We work through one together, and another and… “Wait! I predict the answer is 15!”

“Holy moly, Philip! It is. How did you know that?”

“Because you have five ones and you just add a ten!” We high-five. We cheer. He rushes through the whole rest of the sheet, with more high-fiving and more cheering. Before he leaves, he asks for a whole bunch of sheets for homework. Which, his mother reports, he completed all in one sitting.

This morning, I pull out the Adding Ten missing factor worksheets. They are still pretty boring and look almost exactly the same, but have the one-digit number replaced by a square that needs to be filled in.

“We are going to do a slightly more challenging one today. But you can do it.”

“NO! I’m not ready for a challenge. Give me the easier ones I can do. I don’t want to learn something new now.”

I have him write out 10 + 4 = , which he solves immediately. I show him the first problem. 10 + ___ = 14. “Wait!” He writes down 4. We high-five and before I even have a chance to ask him if he gets it, he is halfway through the sheet, then done.

“I want more of those for homework! Not just one. More!”

It’s the end of the session and I hand him three. As mom and I are chatting, he zooms through one, and then a second one. I grab the third one and hand it to Mom.

“Come on, Philip. Don’t complete all the worksheets now or you won’t have any for homework!”

No rewards. No punishments. Nothing motivates like success.

How true! Thanks so much for the reminder to all of us.