I sit at the corner of my street and our trafficy cross street, my neck craned to the left, assessing when I can go.

“Go, Hon,” my husband says. “There’s space…Still space…Still space…ok, now there isn’t.”

I am embarrassed to tell you how many times this happens, although no one who knows me well would be surprised. It seems my brain simply cannot process how far away are those cars hurtling through space, nor how quickly they will reach us, so as each one comes into view, I am positive it would plow right into me if I went. Apparently, given how many times I am “politely” honked at, I am almost always wrong.

It’s not that I’m dumb. In fact, by all traditional measures, I’m quite the opposite. I was extremely successful at all things school. Loved reading. Loved writing. History, science, math, loved, loved, loved. Heck, I could probably still remember the formula for figuring out the speed and distance of a moving object, because I even loved Physics. Yet, I still need my husband to tell me when I can turn onto a busy road.

I have thought about this apparent contradiction ever since I learned about multiple intelligences and neurodiversity. Which is to say, ever since I started to teach.

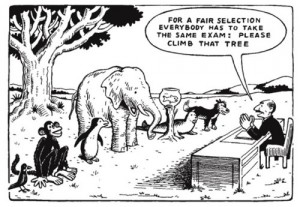

I recently attended a conference at Harvard’s Research Institute for Learning Disabilities, and was struck by one theme running through every single speaker’s presentation. Dr. David Rose said, “Learning differences are an expression of normal human variation. Learning disabilities are an expression of variation in the environment.” In other words, what changes a learning difference into a disability are the specific requirements of a situation and their mismatch with a student’s inevitable human neurodiversity. Dr. Deborah Waber puts it this way: all learning disabilities are an outcome of the child-world interaction.

Living in California, I think of it like this. Way back in time, before buildings, earthquakes were freaky and weird, but they weren’t dangerous. The danger comes from the buildings, not the earthquake itself. No buildings, no destruction!

The same is true with a child. Their brain may find it difficult to parse out the individual sounds in words (the phonemes), but that on its own does not a disability make. Three thousand years ago, heck, three hundred years ago, when pretty much everyone was a farmer, who cared? But put that child in a classroom where they are supposed to learn to match those phonemes up with letters (graphemes) and voilà! Dyslexia. No reading requirement, no dyslexia.

You can follow this logic for all of our current “epidemics.” ADHD? As Dr. Kathleen Nadeau points out: “ADHD is a function of compulsory education: the idea of children sitting down quietly and listening for six hours is a bizarre notion.”

This understanding of learning difficulties makes me think about the many students I have worked with who struggle with academics. Most of them have enormous strengths, which are, unfortunately, simply not considered important in the context of school.

I think of one blond third-grade boy I taught whose artwork showed a maturity and control unusual in artists twice his age. It was certainly better than anything I could ever draw. This kiddo, who struggled so mightily with reading and writing, stopped me one day as I was trying to shove a big box of supplies into a spot on a shelf that I thought was just perfect. “You know that won’t fit, don’t you?” he said.

“Are you sure?” I asked hopefully (ok, maybe stubbornly), as I continued to try to cram it in.

“Just let me handle it, Ms. Kennedy,” he said as he shook his head sympathetically and took the box from me. About ten minutes later he had the entire cabinet reorganized in a much more orderly and efficient manner. There was my box, and plenty of extra space as well. I sighed as I thanked him. “It’s ok, Ms. Kennedy,” he reassured me.

He’s in Middle School now, and I haven’t spoken with him in years. I wonder how his self-confidence is holding up now that he has to write essays and read longer novels. I wonder if he still shows his teachers his amazing artwork and his complex thinking, or if he has learned to be invisible so no one will call on him to read aloud.

And here I am, a teacher with two Master’s Degrees, an Educational Therapy certificate and GRE scores to die for, waiting at the corner of the road for my husband to tell me when I can go. The question occurs to me for the millionth time as I inch out into traffic, who really has the learning disability?

copyright Diana Kennedy 2014

Well written and explains exactly the frustration of the label called learning disabilities. Every person has a gift.

Thanks!

[…] I sit at the corner of my street and our trafficy cross street, my neck craned to the left, assessing when I can go.Is it clear? […]

[…] as being not so much a “learning” disorder, as a “print” disorder. As I have mentioned in previous posts, Dr. David Rose points out that all learning disabilities are in truth a function of normal […]

Such a beautifully written piece, and incredibly insightful! If only the “powers that be” that mandate testing could consider these thoughts and realize that my students are human beings….NOT widgets! Just as two snowflakes differ….so do my kiddos!

Thanks. I absolutely agree.

Nicely put!

Diana, if you are near Long Beach, you might like to stop in to talk to Helen Irlen, whose Spectral Filters really help with depth perception. Short on time? Try http://www.irlen.com to see if you find information there. Cathie Hay

Thanks, Cathryn. You are sweet. I live in California, though. I do know some excellent vision therapists and have been toying with the idea of going to one of them. But for now my “accommodation” of having a patient husband is working out. :-)

Excellent post. I agree with it.

I completely agree

[…] I sit at the corner of my street and our trafficy cross street, my neck craned to the left, assessing when I can go. “Go, Hon,” my husband says. “There’s space…Still space…Still space…ok, now ther… […]

Thank you for such a kind, open, informative essay. A brilliant read.

Thank you for your very generous words. You’re welcome!