When I was a teenager, my room was filled with unicorns and rainbows: posters, stickers framing the mirror, and my prized possession, a hanging rainbow, an ingenious decoration with thin strings threaded through a wooden circle, cascading from almost the ceiling to the ground, creating an eight inch in diameter column of silky rainbowness.

When I started teaching, I carefully placed my rainbow column in a corner of the room for the kids to see, touch and enjoy. Needless to say, they loved it. And perhaps even more needless to say, their love constantly tangled the thing up. Every few days I’d spend twenty minutes after school patiently untangling the silky strings from the top down.

In my second third grade class, I had a student who may perhaps be the sweetest girl ever to live. Diminutive, caring, soft-spoken and loving, Norma* loved school, loved and was loved by her classmates, and loved and was loved by me. She was forever doing sweet little helpful things, cleaning up the library, straightening up the Band-Aid box, picking trash up of the floor.

One day, in the middle of teaching, I looked over and saw her very carefully working to untangle the rainbow column. With scissors. I couldn’t stop from a kind of gurgled yell of her name and something akin to “What are you doing?” She looked up at me and in a few nano-seconds, went from looking pleased to be helping me to mortified that she did something wrong. I did my very best to swallow my emotions, knowing that any tear I shed right then would be a dagger in her eight year-old heart. I breathed deeply and reassured her that I knew she was trying to help, and kept repeating that as I took the ruined column to my desk, blinking hard to stay in control of my emotions.

I tell this story because it is an obvious case of what may be the most key realization for a teacher to have. I was lucky that Norma’s transparent expression counter-balanced my sense of loss with the crystal-clear understanding that my feelings were about my loss, and not at all about her intentions.

Throughout the school day and year, especially in less obvious situations, one of the most important things to keep in mind as a teacher, or even as a parent, is the gap between how a student makes you feel and what the student intended. Your student’s hurtful, mean, disrespectful, disruptive behavior? It’s not about you.

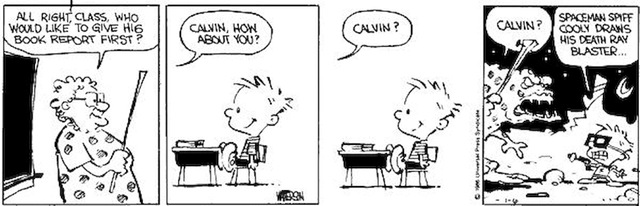

Teachers, as the representation of Adult Authority in the classroom or office, often bear the brunt of a student’s complex emotional responses to authority, school, parents, learning, their feelings as a student, their feelings as a peer of other students, yet we have little or no training on interpreting their behavior as a form of communication. Therefore, we are apt to take everything a child does personally. We feel fully human with our own internal lives, but, if you remember way back to your own childhood, you know that children simply don’t see teachers that way. Think of how Calvin, of Calvin and Hobbes, feels about his teacher, Mrs. Wormwood.

Love us or hate us, how they treat us is not actually about us.

I had a colleague at a school once who came into the teacher’s lounge fuming. She threw herself into a chair in frustration and said, “That Frank*, he just tried to make me look like an idiot in class!”

For a little context, Frank was a sweet but awkward, well-meaning fourth grader with mild Asperger’s.

“After I told the kids a story, I was talking about what it meant, and he butted in and said he had heard the same story, but it meant something different. He was trying one-up me, to challenge my authority, to make me look stupid. I thought we had a good relationship, but now I think he hates me.”

This teacher had let her strong feelings completely overwhelm her. Rather than looking to see what Frank’s actions might mean to him, she conflated her feelings with how he intended to make her feel. She ended up punishing Frank with harsh words and a call home for something he had no idea he had even done.

Now, I knew Frank and knew that he 1) loved this teacher, 2) wanted her to like him, and 3) equated her liking him with her being impressed by his knowledge in her subject. Far from trying to embarrass her, he was trying to impress her and make her like him more. The fact that he used showing off as a way to gain approval and friends was a good insight into why he annoyed so many of his peers, and perhaps a window into his life at home, but it certainly had nothing to do with his teacher.

So for your sake, and the sake of your students, when you find that kid, the one who gets under your skin or drives you nuts, take a deep breath and look at what your reactions can teach you about yourself and about the child, but for goodness sakes, remember that it isn’t about you.

*student names have been changed for anonymity

copyright Diana Kennedy 2014

[…] post: It’s not about you copyright Diana Kennedy […]

Having been, as a child, mortified when a teacher accused me of misunderstanding a math problem on purpose, to deliberately bother him–I truly wish this could be required reading before any teacher was allowed in the classroom. So much trauma could be avoided!

That’s terrible. Seriously, what child would act dumb to annoy a teacher. Students will do almost anything to avoid being seen as dumb. It’s mind-boggling.

That was a very well written post. As a psychologist and a mother, I love your insight into the children’s behavior. It is so easy to interpret children’s actions as intentional towards adults when their actions are much more reflective of their own stage of development.

I agree, that is always important to not take things personally. In teaching individuals with autism spectrum disorder ASD, I have often encountered challenging behavior from students, some even physically aggressive. This behavior even the physically aggressive behavior was not about me. Often it was an attempt to communicate in a child with an impairment in his or her ability to communicate. Children with ASD have impairments in communication, social skills, and have repetitive movements or preoccupation. Individuals with Asperger’s, which now classified ASD, have deficits in social communication. They tend to be preoccupied by a certain topic, and can be pedantic (like a little professor). The boy with Asperger’s corrected his teacher because he really did not know he shouldn’t. The social rules we all seem to just know from birth are not accessible to him because of the way his brain works. A famous author Temple Grandin, who has ASD refers to it as being an “anthropologist from Mars”. Individuals with Asperger’s do not develop a theory of mind (ability to perspective take) and this makes situations like the one where he corrected his teacher or annoyed his friends common. There are methods to address these social deficits and student with ASD should have access to them.

I agree. I think one of the best insights of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is that all behavior is communication. It is true about all students, and, as you point out, even more true about kids with an ASD.